When Eric Schaeffer, the tireless director of the new Kennedy Center production of Follies, first approached Gregg Barnes and asked him about “doing the costumes,” the Tony-Award-winning designer said, “Let’s talk first. Let me do a few sketches, and if this ain’t it, I’ll politely bow out.” Barnes, who cautions he would “sell his mother into slavery” to do Follies, thankfully didn’t have to make that choice. In fact, this is his third time costuming the show that had a short original Broadway run but established a super-sized reputation.

“It’s such a hard show,” he says. “It’s not the biggest, just the most expensive. I’m trying to make it look like a million bucks. But I don’t have a million bucks.” The buoyant and affable Barnes has done his homework. He designed the cultish Paper Mill Playhouse production in 1998. (“They renamed the Amtrak to Millburn, N.J., the ‘Follies Express,'” he explains, “because of all the famous people taking the train out to see Ann Miller.”) He also co-designed, with William Ivey Long, the 2007 Encores production. Barnes has a long list of Broadway design credits, including Side Show, Legally Blonde, Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Elf and his Tony winner, The Drowsy Chaperone.

But this production of Follies puts him in a unique position. He believes the original 1971 production is so beloved and seminal that it must, in some way, be honored. In discussions with Schaeffer, whom he describes as a uniquely gifted collaborator, they examined the darkness in the story and the rich complexity of the score, huddling over ghosts and memories. Barnes says all the characters in Follies are still alive, and their ghosts are as curious about what has happened to them as the people in the present are, looking back on their pasts with that wistful nostalgia we often have about our youth. Operating simultaneously in the past and present, he has worked to find a vocabulary that allows his ideas, like layers of clothing, to be revealed slowly and deliberately.

Taking the strong image of a “broken feather,” he has designed ghost costumes that are somehow disintegrating – a sharp contrast to the young and dewy cast members. “Things are not perfect,” he says. “You may have a Follies gown that once had a magical quality to it, but after 50 years of wandering through the theatre, it’s slowly sinking to the floor. It’s picked up a lot of crusty old pallets and pieces.” The Young Sally and Young Phyllis wear, according to Barnes, a spectral print that comes and goes like a memory, but also is reminiscent of the period.

When he showed his initial rendering to Schaeffer and Warren Carlyle, the choreographer, they thought it looked like a girl who had been sitting in the window of the worst dressing room in the theatre – somewhere on the seventh floor – just waiting to see what happened with her life. Barnes took that idea and had the dress painted so it looks as if it’s faded across the body, bleached by the sun.

“But I do it in a way that is subtle enough to respect the actor and not call too much attention to itself. What I am trying to do is illustrate that the characters are dragging this burden around now. I want to make it look like there is just a breeze blowing across the stage and they are light and magical, just a vision of an apparition.”

Of course the original Ziegfeld Follies looms imposingly over the designer’s work. Many of our notions of what these early Follies were like are based on the Hollywood films of the 1930s that, to some extent, were inauthentic. One of Barnes’s most intriguing inspirations was a book of publicity photographs he gleaned from a rabid collector of Ziegfeld memorabilia. Featured prominently in the book are photos of Doris Eaton Travis, at the time of his research the sole surviving Follies dancer at the age of 106.

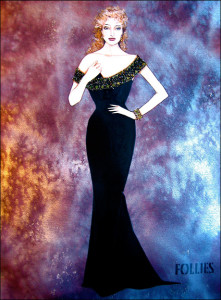

“There’s a tribute to her life on YouTube, which I’ve watched about 10 times,” he says excitedly. “But I have to ‘man up’ for it because I’m just a mess when I watch it.” Barnes considers Travis’s life as an allegory for these Follies – aging, lost dreams, unquenched desires. In one photograph she is shown wrapped in a piece of tulle beaded with sequins and pallets like a halter dress. “It’s a flame to seduce,” he adds. “I used that more than anything else. I had this notion that the gowns were falling off so the upper body is very fragile.”

Other ideas came from the score itself. Barnes was very specific with Heidi Schiller. She’s the oldest character at the party. If the first Follies date we are privy to in the text is from 1918, then she was there from the very beginning. “Her ghost needs to live in a Victor Herbert ambience. The flip of that are Phyllis and Sally and a few of those ladies who were in the most “recent” Follies, in 1941. The spirit of those memory characters is from the 1940s.”

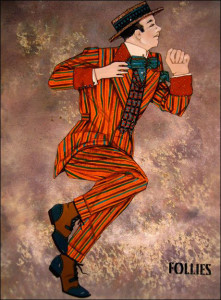

Barnes says he pushed the envelope a bit and made the Heidi memory more Victorian and the younger Phyllis and Sally at the cusp of the early 1940s. Photos of Ed Wynn helped to inform “Buddy’s Blues,” as did images of the dapper Fred Astaire with Ben, clothed in a beautiful midnight blue suit without any beading, surrounded by everyone else swimming in beading for his breakdown Follies number.

“He’s the calm in the storm on the outside, but on the inside, of course, it’s a different story. It’s a kaleidoscope of information, history and even the audience’s memories. You look at all those things but you also look at what Galliano did on the runway and mixmaster all of these things together to come up with good storytelling.” And Barnes can certainly do that.

“You know Bernadette wanted to wear a red dress when she makes her entrance to the party,” he says elfishly. “Dorothy Collins wore a frothy thing in the original, and Donna McKechnie wore a pink frilly thing at Paper Mill. Of course, I had a moment of ‘wow,’ but we talked through the logic, and it made perfect sense to me. Sally has come to seduce.”

The color red has figured prominently in his designs for other Follies productions. At the Paper Mill, Liliane Montevecchi, a person of decided opinion, according to Barnes, would only wear camel, black or red. “We didn’t want that character in black because it would blend into the ghost world, and camel is actually nude, so I told the director if you want Liliane she gets to hold the red card.”

Shortly thereafter Barnes and Ann Miller were in a telephone discussion about what her character would wear in the same production and he said, “We’re thinking of putting you in black,” to which she replied in her characteristic voice, “Black? I’ll look like shit in that. Her name’s Carlotta. I should be in red.” And in his panic Barnes told her that nobody would be wearing red, hung up the phone, and worried for a month, thinking, “Miller’s going to show up and there’s going to be a French woman in a red dress.”

Thankfully, it all worked out. Barnes understands his cast members and having read Miller’s autobiography knew she believed in reincarnation. He schmoozed her with an idea that Carlotta was a person who thought she was reincarnated from an Egyptian queen and told her, “Wouldn’t it be interesting if she wore a dress in lapis lazuli that had a big lotus on the front,” and Miller replied, “Keep talkin’ honey. I love where you’re going.”

If the ghosts and memories of Follies inhabit their characters, Barnes has had his own with which to contend. He grew up in San Diego and remembers, as a kid, subscribing to Theatre Crafts magazine and reading an article about Follies. There was an interview with Florence Klotz, the original costume designer, and Barbara Matera, the owner of the premier costume house serving the New York theatre. There were photographs of magical, extravagant visions, and they stuck to his brain like the beading on one of Adrian’s dresses. Cut to 1985 and the famous staged concert at Avery Fisher Hall. Having listened to the original cast album “about 10,000 times,” he was a serendipitous recipient of one of the coveted tickets. “It was the first magical time I had in the theatre, ” he fondly recalls. “Barbara Cook sang ‘In Buddy’s Eyes,’ and we were suspended on a breath. And then, in unison, a roar. I had never heard anything like that. I was afraid people would throw themselves off of the balcony to their deaths.”

And so this 2011 Follies production, he felt, must amalgamate memories, recollections and tributes. The ghosts of Florence Klotz and Barbara Matera will be there on the “Weismann” Eisenhower stage, along with headpieces created Paper Mill production by Woody Shelp, the well-known theatrical milliner, who died in 2004. Barnes calls him “the Stephen Sondheim of hat makers.”

Barnes says, “Everything we do is for the actor, to help that character tell the story. I love the well-cut suit, the exquisite dress. But I only really care about them in relation to storytelling.” After all, that’s where the ghosts of Follies, past and present, meet to put on their clothes.